this is the autumn I learned to tie my hair

into a twisted bun with a brass hairpin

I learned to accept the drizzling rain that

slipped under my skin and combed through my blood.

this is the autumn I learned to let words

linger on my tongue and taste their flavor.

I folded my stories into paper cranes

and sealed my poems in a mason jar.

this is the autumn I dipped my sorrow in lemon tea

and watched it swirl and curl into bitterness.

I took off the pearls of laughter

and put on a gold chain of silence.

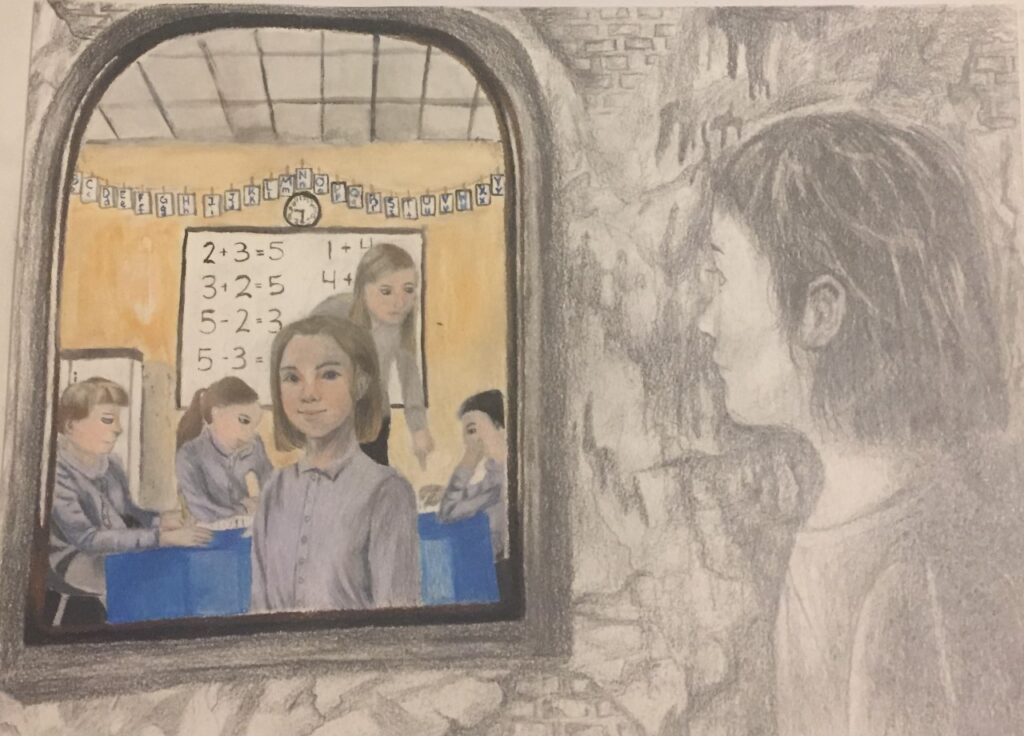

this is the autumn I became a different me

Allison Xu is a teen writer from Rockville, Maryland. Her work has been published in Unbroken, The Daphne Review, Germ Magazine, Secret Attic, Spillwords, Bourgeon Magazine, The Weight Journal, and others.