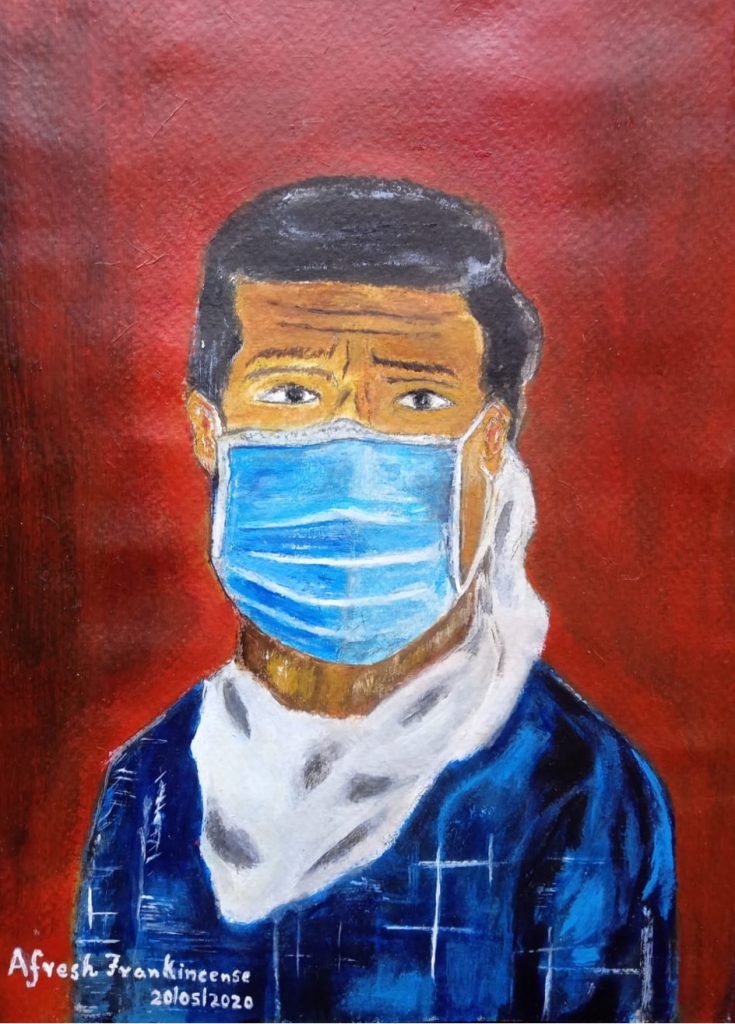

Afresh Frankincense is twelve years old and in Class 7th. He’s a child art-prodigy and writer from Odisha and lives in Hyderabad in South India. Though he loves math and science so much, art has a special place in his heart. His work appears or is forthcoming in The Elephant Ladder, Moonchild Magazine, The Celestial Review, The Ekphrastic Review, Kids 4G and elsewhere.