Alma wasn’t dead.

She was almost sure. There were no angels, or hallelujahs, or blinding golden halos made of children’s dreams. Or whatever. St. Someone hadn’t escorted her past pearly gates, saying, “Congrats, kid, that was the hard part.”

Then again, that’s not where she’d end up, according to her mother. Alma liked to kiss girls and slip especially pricey nail polishes into her pockets, so it was important to note that there were also no fiery pits, tortured politicians screaming, or a hooved man patting her on the back, saying, “Sorry, kid, that was the easy part.”

And one of the girls Alma liked to kiss was Hindu, so in the spirit of fairness, she should acknowledge that she also had not been reborn into a new body. At least, not obviously. And her freshman roommate was a pessimist, so Alma also took the time to confirm she wasn’t “like, literally just worm food rotting away in the ground.” She was not.

What Alma was, once she stood up and looked around, was alone. Alone in a small graveyard, if one could ever truly call themselves alone in a graveyard. She had been lying next to a headstone, and the headstone’s bouquet of polyester daffodils. Her jeans were dirty, her boots scuffed, though that was not new.

Looking around in the faint light of sunset— no, that was east. The sun was rising. She knew a compass tattoo would be useful one day. Looking around in the faint light of sunrise, Alma examined the headstone she had been so comfortably unconscious next to. The name meant nothing to her, the dates even less. No hints. She checked her jacket pockets. In the left, $25.85, her ID, and a bottle of no-chip “Leapin’ Lilac”. In the right, a switchblade and a single glove.

Disappointing. She had been hoping for a note from last night’s self, saying something along the lines of, “If you’re reading this in a graveyard with your memory wiped, we’ve just won $10,000!” She checked her jeans pockets. In the back left, an additional $0.25. In the back right, a slip of paper, though she immediately knew it was too small to be her saving grace. Squinting, she read the fortune from a long-since-eaten fortune cookie: “Depart not from the path which fate has assigned.”

Alma looked around once more. A thin trail of flattened grass in the graveyard led to a crosswalk, which sort of led to a little lit-up diner. Maybe that was too literal of an interpretation, but she was hungry. There was just one car in the parking lot, and one bicycle propped up against the wall.

Returning the fortune to her pocket, Alma crossed the road.

***

Sylvia wasn’t dead, but she sure felt like it. The early morning shifts at the diner put a special kind of weight on her bones, a whole new kind of pulse in her head. She was too old to be up with the moon, awake before the sun, but she supposed she did it for the company.

Some company. The place was empty, save for the silent cyclist at the farthest booth and Elvis on the jukebox. The place was almost always almost empty since James had passed eight years ago. He used to come in every morning for breakfast, sing along, and chat with her about his plans for the day. The thing Sylvia missed most about her husband was their chatting.

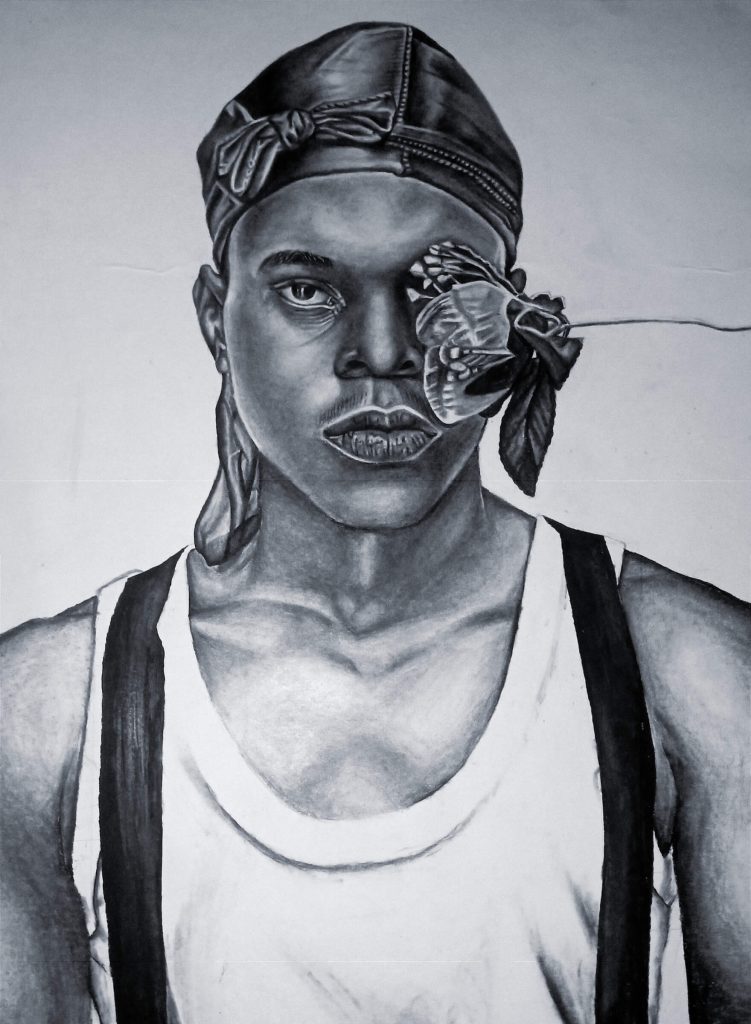

The bell rang. A girl, about twenty or so, interrupted “Are You Lonesome Tonight?” as she opened the door and walked in. Her dark skin was home to darker circles under her eyes, and she wore ripped and muddy jeans. Kids these days— purposefully trying to look grungy, or dirty, or tired. Sylvia couldn’t keep up.

The cyclist shut his notebook, stood, and hurried out into the cold as the girl made her way toward the lunch counter. She sat down and ordered a coffee, black, a slice of apple pie, and a map. Any map, if they had one.

“Want a fortune cookie too? Free of charge.”

“Oh. Sure.” The girl tilted her head. “Uh, is this diner Chinese?”

“No, but neither are fortune cookies. Invented by a Japanese immigrant in California, or so I’ve heard.”

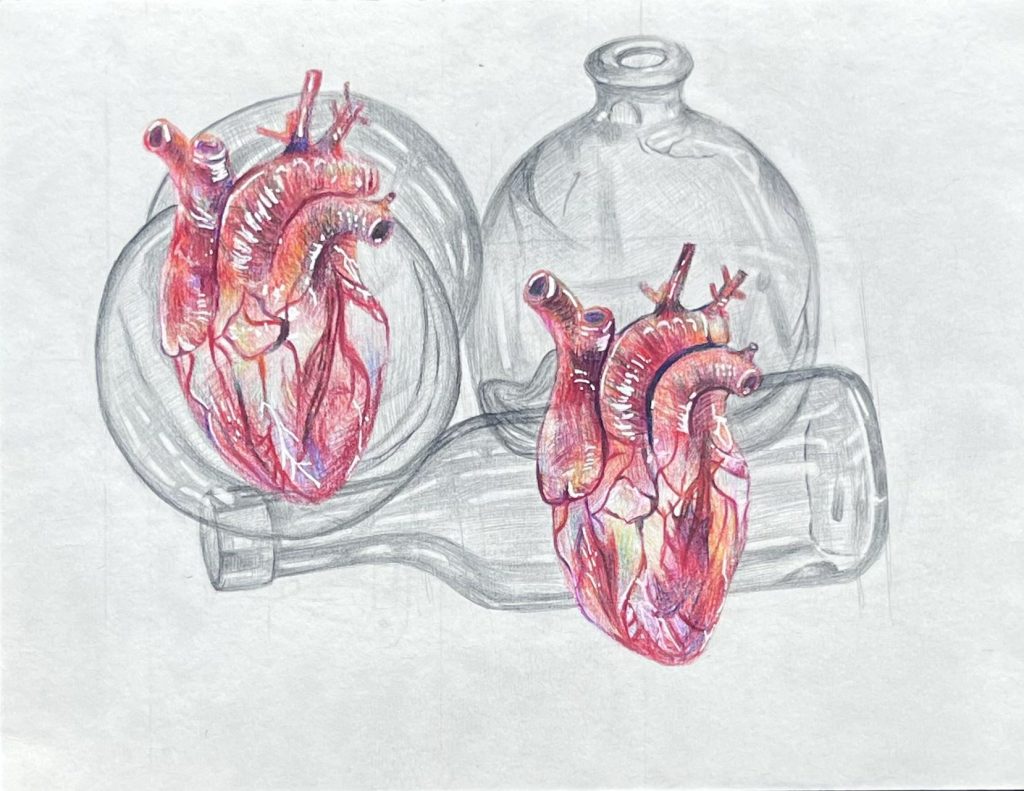

Sylvia ducked down and grabbed four cookies from the bin below the counter. She placed one in front of the girl, and three in front of herself. “I always read three and go with the fortune I like the most. People tell me that’s not how it works, but I say if you have the opportunity to cheat fate you should do it. And they’re really not that expensive.”

The girl “Mm-hm”ed into her coffee and studied the map. Sylvia broke the three cookies before her and laid out the small slips of paper.

“‘Kindness is contagious,’ ‘the nightlife is for you,’ ‘and a feather in the hand is better than a bird in the air.’ Second one definitely isn’t true, at least anymore, and I have no idea what the third one talking about, so I guess I’ll go with the first,” she said after considering for a moment. “You gonna open yours, hon?”

“Yeah, sorry. Um, it says, ‘You’re exactly where you’re supposed to be.’”

“That’s nice. I can take the map back and give you a job application if you want. We could probably use a youthful touch around here.”

The girl didn’t respond, but refocused her attention from highways and rest stops to the pie. She ate slowly, considering the diner around her.

Sylvia grabbed one more cookie from the bin. Sometimes, only sometimes, she would try four if the previous three fortunes didn’t appeal to her. She sat back and read the short sentence she had pulled out: “Someone is eager to speak to you again.”

She smiled, grabbed her keys and her purse. Her shift was almost over, anyway. James was in need of fresh daffodils— he never liked the fake flowers. Sylvia was almost certain that’s what he wanted to talk about.

***

Leo wasn’t dead. This was something he had just realized.

He was sitting in the corner booth, the one he had sat in every night. Well, morning, more accurately. The sun was rising. He always sat in the back, politely ignoring the chatty waitress whose name he could never remember, and whatever old song was playing too loud. He ordered an omelet. Then he would bike around town, waiting for the next morning to come. He liked the familiarity of the routine, even if he wasn’t fond of the routine itself. He biked, sat, ate, and breathed the same way, every day.

Lately, though, the routine had felt a bit overbearing. Leo could ride his route with his eyes closed. The corner booth was directly under a freezing air vent. The omelets tasted like bland, broken dreams. He thought way too much about how he was breathing.

Fearing he’d lose the will if he waited too long, Leo shut his empty notebook and pushed his uneaten omelet aside. He left some cash on the table and walked out the door, passing a girl he hadn’t seen before on the way. It was unusual for Leo to have not seen someone before, and he might have stopped to ask for her name or why it looked like she had just been rolling around in dirt, if he had not been so determined to leave.

He grabbed his bike and went straight through the crosswalk toward the cemetery. He held his breath as he arrived at rows of headstones. Leo had read, in one of the fortune cookies the waitress (Sally? Cindy?) had given him, that inhaling near graves would allow spirits to enter your body. He guessed they were looking to hitch a ride and get out of this town. He couldn’t blame them— he was looking for the same thing.

It had seemed like a weird thing to be in a fortune. Weren’t they supposed to be predictions? Leo went against the cookie’s advice as he decided it would be more interesting to bike through the cemetery than on the sidewalk. Look at that. His new routine-breaking life was starting already.

He biked past rows and rows of names and dates, some simple, some intricate. Some had flowers, most did not. He stopped at one with a yellow bouquet to smooth out grass and dirt that had been messed up. Leo smiled at the name carved into stone before him. “There you go, James. All fixed up.”

Maybe in his new life, he’d be the type of person to talk to spirits, let them hitch a ride. Maybe he’d worry about his breathing a little less. He never had much luck with fortunes, anyway. The last one he got said, “You love Chinese food”. He thought Chinese food was just okay.

Lauren Mills hails from a small town in North Carolina and aspires to own many, many cats.