Patricia is a grade eleven student in Toronto, Canada who loves writing, film, fashion, and philosophy. She also wishes she could add to this bio, but can’t really think of anything. You can reach her at @_patriciaphobic_ on Instagram.

Literary Journal for Young Writers

By Patricia Zhang

By Sabrina Xu

By Sholanke Boluwatife Emmanuel

By Audrika Chakrobartty

Audrika Chakrobartty is an eighth-grader who lives in Texas. She enjoys writing,reading, drawing, and listening to music during her free time. She’s also an avid artist, working with all types of mediums, but her favorite one to work with is just pencil and paper. She also enjoys creating watercolor/oil paintings.

By Hans Gupta

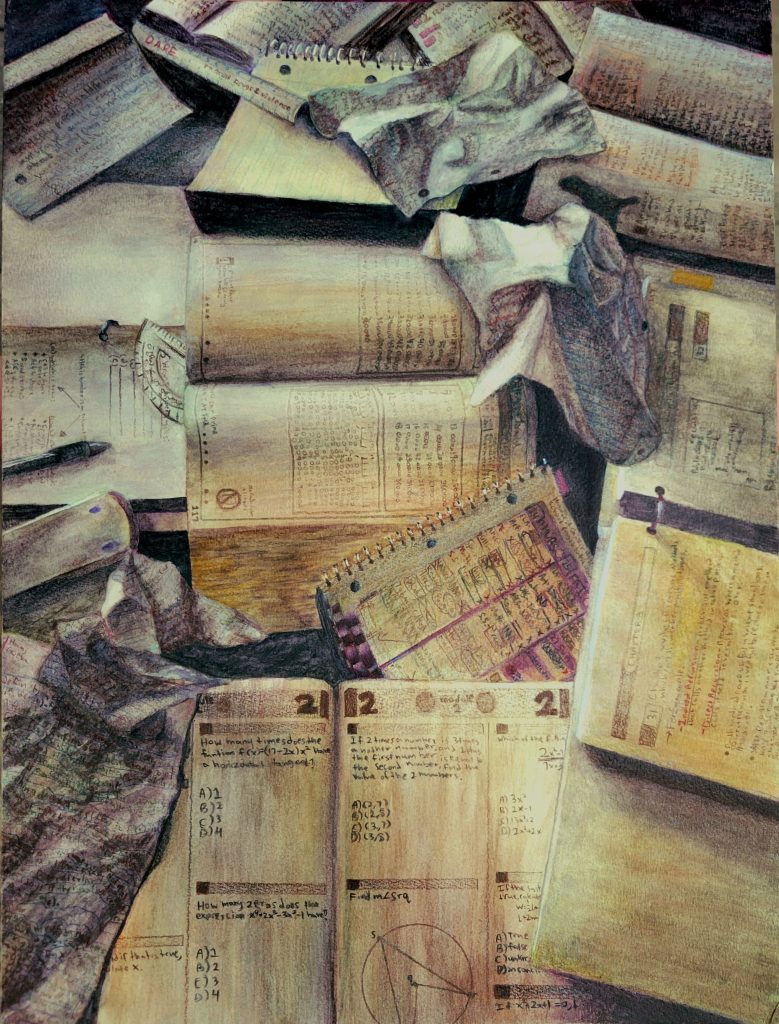

Hans is a sixteen-year-old, Indian American, male from upstate New York who has, alongside mathematics, passionately pursued art since young. Now, as a high school student in junior year, he’s looking to go further with his art skills and publicize his work. On a more personal level, he puts a high value on academic excellence, sports (Tennis and Badminton ), and individual nuances or hobbies that add texture to a well rounded person.

By Diya Maria Tom

Talking about the Kerala chai requires a geographical explanation of the land that is even titled as God’s own country, where the emerald green landscapes meet the bright blue embrace of the Arabian sea. But amongst all this charm, it’s the evenings at home that truly transport you to a dimension of artistry, emotions, and sweetness beyond compare.

The evenings are always different. It can be a warm, golden embrace that caresses the lush green landscape, or sometimes after the morning rains that quenched the thirst of the earth, the evenings bring a refreshing change to the sky once heavy with clouds, now wearing a duet between the royal purples and the most ethereal blues.

Our home is nestled amidst a lush sanctuary of trees, both big and small. The big trees with their sprawling canopy and the delicate flowering plants that hug the fence co-exist in the harmonious surrender to nature’s rhythm. The mango trees in our front yard are in full bloom, their branches heavy with fragrant blossoms, a perfume that lingers on the senses. It is as if the very essence of Kerala’s summer has been captured in those blossoms.

Snacks play an important role in the illustrations of evenings in Kerala. They are not just culinary creations; they are incorporations of generations of culinary understandings, wisdom, love and tradition.

Imagine biting into a crispy golden brown yet yellow sphere that crackles like autumn leaves underfoot. This is the magic of the lentil-stuffed sukhiyan. As you take the first indulgent bite, your taste buds are met with a sweet surprise – a luscious, fragrant filling of cooked green-gram in jaggery and grated coconut, infused with love and the flavors of cardamom. As the effort I put into explaining sukhiyan would explain my love for them, there are also other snacks like neyyappam, and vattayappam. And how not to mention wonders created with plantains,— and impossible not to mention a malayali’s relationship with tapioca, with love – kappa. The creativity and ability of Kerala home cooks to turn a humble root into boiled or crispy , savory chips and much more.

Sitting on the porch, as we sip our chai with some homemade snacks, the warmth of the cup in my hands mirrors the warmth in my heart.

Neighbors pass by with their cows, heading back home after a day of grazing. An everyday sight that adds rustic charm to our village, we exchange pleasantries, wits and stories, connecting in a way that only happens in tight-knit communities. The rhythmic clinking of cowbells accompanies our conversations, blending seamlessly with the philharmonic evenings.

My grandmother, a living storehouse of wisdom and love, joins me. Watching the world go by, her wrinkled hands, adorned with simple undecorated gold bangles that chime like music effortlessly find their way through my hair, massaging my scalp with a fondness that words cannot express. Her touch is a balm to my soul, an unspoken reassurance that I hold dear. A very simple gesture that spoke of a lifetime of care and affection. Our conversations about life, her advice, stories, her patiently listening to me, her beautiful smile filled with innocence and all that love, together makes all those moments very special.

As the stars begin to twinkle in the velvet sky, nature quiets down, the only sounds are the crickets. It’s a moment of serenity, a reminder of the beauty of simplicity. Whispering “good night” to the rustling leaves, I carry the evening’s magic with me to my dreams.

An aspiring healer with a passion for words and a stethoscope around her neck., Diya Maria is a Tennessee- based nursing student. A devoted reader and an art enthusiast, she tries to bring unique perspectives to the pages that resonate with the heartbeat of readers everywhere.