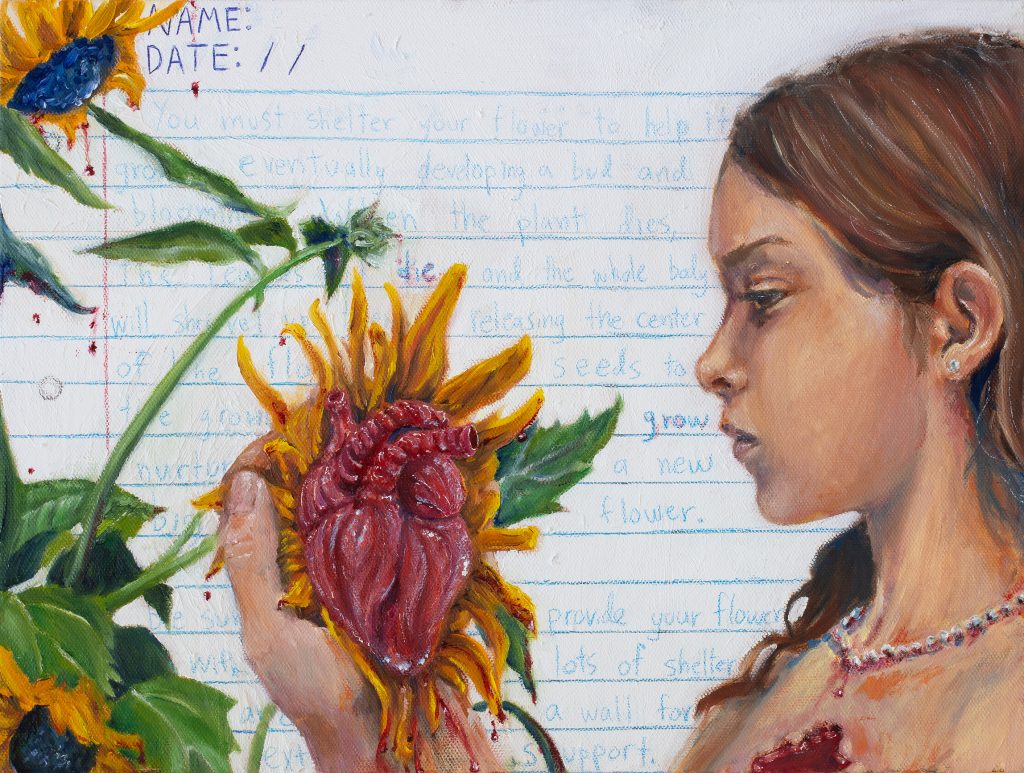

Rana Roosevelt is a digital and traditional artist in Philadelphia. She is a rising senior, and hopes to continue creating pieces in college.

Literary Journal for Young Writers

By Rana Roosevelt

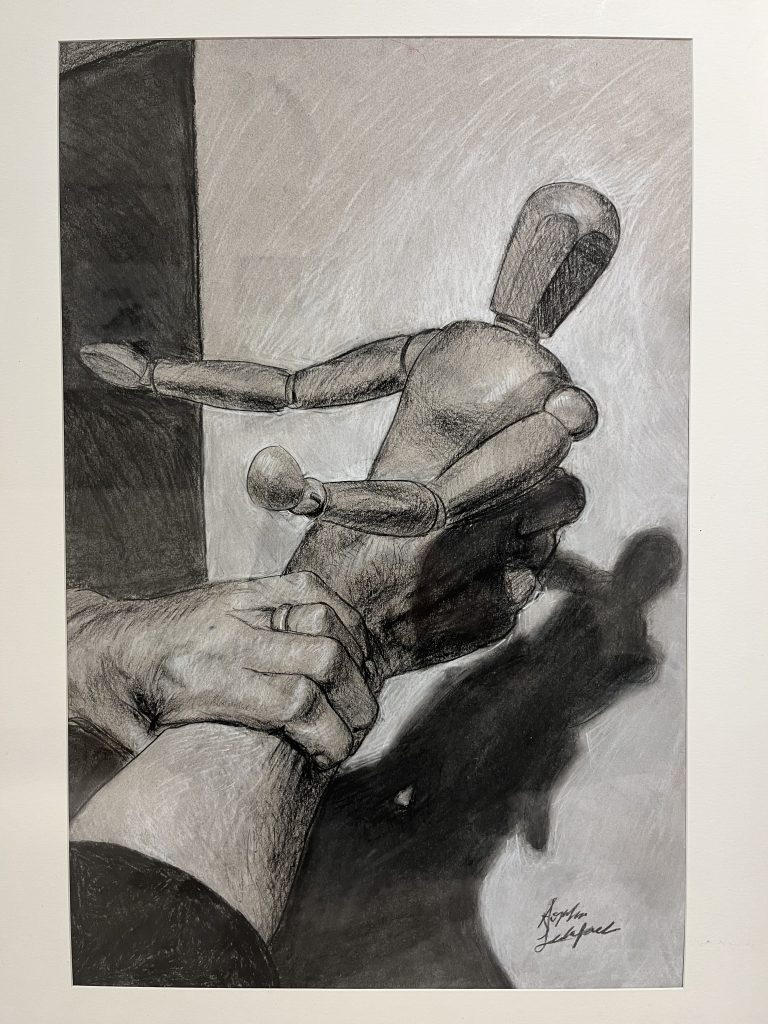

By Sophia Lekeufack

Sophia Lekeufack is a first-generation high school junior based in the Washington DC Metropolitan Area. She has been published in Roi Fainéant Literary Press as well as recognized by the Scholastic Art & Writing Awards. Through the mediums of poetry and prose, Sophia amplifies not only her stories but the stories of those who came before her. If she is not lying in her bed reading a Patti Smith memoir, you can find her at the local Thai restaurant devouring some drunken noodles.

By Sally Young

I’m espresso

As the romantics say

In the way that I energize & entertain

Add some cream and you’ll be set

I’ll be sweet

It’ll be brief

But, as I’ve learned,

I’m espresso also

In the way that too much of me

Makes you jittery

A punch in the gut before I leave

No, I know you’ll hightail it

At the tail end of your high

After a bit of steam

And the hope of being held—

it gets to be enough, too much

And then I put you to sleep

Sally Young is an emerging poet studying Creative Writing at Dartmouth College. She has previously published a poetry collection titled Light Through the blinds, and hopes to keep refining her craft to better the world.

By Yufei Xian

Today’s theory

or rather, hypothesis:

one’s trajectory changes

completely every 1095 days.

Evidence:

2190 days ago,

I stepped foot upon this foreign

home. 1095 days ago,

your materialized in my life’s script,

your radiance disrupting my procedural

existence. Today,

we passed by, mere silhouettes

not a word more than “Excuse

me.” Variables:

How many cycles of 1095 days compose one’s

youth? Where will we be, after the next 1095

days?

do you still think about me too

Yufei (the word itself depicting the poetic imagery of rainfall in Chinese) is a high school student and aspiring writer living in northern California. She relishes in weaving her daytime reveries and nighttime fantasies into the assuaging tapestry of literature. When away from the pen, you can find her playing Studio Ghibli music on the flute, exploring local mountainous trails, or watching a captivating courtroom drama.

By Haynes Melchior

Red light.

we’re stopped at the intersection

of Past and Future.

time is frozen for a moment –

our lives hang suspended in a

fragile balance under a

wash of crimson light.

raindrops refract the carousel

of headlights whizzing past,

making them look like blinking

strands of Christmas lights.

music dances faintly out of the radio

and our linked hands rest

on the center console between us.

I want to capture this moment

preserve it in a jar, like an ant

perpetually suspended in

a teardrop of amber.

tuck it into a corner of the world

where time will never tarnish it.

please don’t change

please don’t forget me

please don’t let go

Green light

Haynes is a writer and editor for her high school’s literary magazine. Her work has been published by the Florida chapter of Poetry Out Loud Gets Original.

By Eartha Davis

Now, my love wakes

to a christening of

birds // his feathers

flutter face-

like // nurse

the dawn’s

receding // if I

hold him, yes,

the world

foams // bloats

under mountain

breath, snow

stubble // worships

the gentle glimpsing

of a human’s

face // what is

waking? // a chapel

of unborn // cotton eyelids

warming themselves,

seeding, a breathing

ache // & little bodies

unwrapping

lightbeds — all that

tendering, all those hands

within

hands, dreaming …

Eartha wishes to live simply, kindly, and most certainly by a river. Her work is published or forthcoming in Wildness, Rabbit, Minarets, Frozen Sea, South Florida Poetry Journal, JMWW, LEON Literary Review, Arboreal Magazine, ELJ Editions, Boats Against the Current, the Basilisk Tree, the Stirling Review, Where the Meadows Reside, Eucalyptus Lit, Uppagus, Discretionary Love, Sour Cherry Magazine, Revolute, & Eunoia Review, among others. She is a poetry editor at three journals and dreams of birds.