I am five years old the first time I can recall feeling ashamed about my heritage.

The lunchtime bell had hardly finished ringing when I, along with my twenty brand new kindergarten friends, come pouring out of the room like jelly beans spilling from a jar — bouncing, clashing, full of sugar.

My stomach rumbles eagerly as I take out my two thermoses.

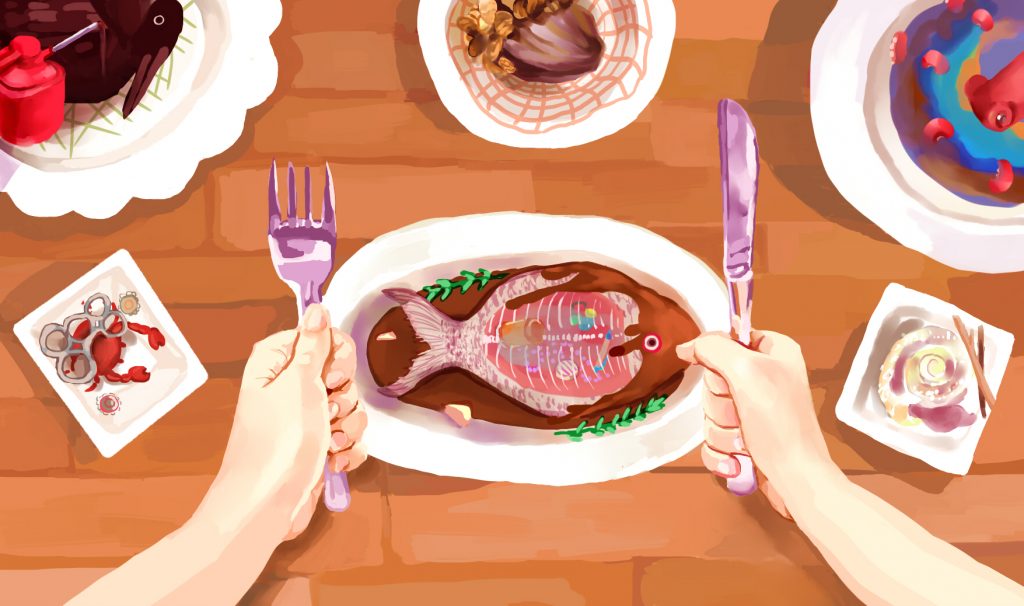

“Two,” my mother always said, “One for the rice, and one for the entrée. You don’t ever mix the two beforehand. The rice will absorb any extra moisture there is.” This wasn’t orange chicken, or broccoli and beef, or anything close to the disgrace, as my parents called it, of Chinese food they sold at Panda Express. This was authentic Chinese cuisine.

As I unscrew the cap of my “entrée thermos,” I let the deliciously pungent smell of chives and bacon wash over me. It isn’t chive dumplings, my favorite, but it’s close enough and smells like home.

Just four weeks prior at the airport terminal, Mama had had no choice but to forcibly peel my hands off of my grandmother’s pant leg as I melted into hysterics, begging Po po not to leave me for the first time since birth.

My doting grandparents had been making chive dumplings from scratch every weekend since I could eat solid food, and at that moment, all my five-year-old brain had the capacity to process was, without my Po po and Gong gong, no one would make me my favorite food.

Struggling to hide the tears in her eyes from me, Po po had grabbed Mama’s hand right as we were about to step into security check, “Promise me you’ll make my little girl her dumplings.” Her voice had caught as she turned away, so I wouldn’t see the tears spill down her wrinkled cheeks. My mother didn’t get a chance to promise.

I glance around slightly boastfully at the other children with their cold PB&J’s, their dry chicken nuggets, their greasy pizzas, and pity them for not having a homemade meal like mine. I grin as I dig into my warm, savory food.

“Ew, what is that smell?” the little blond boy to my right me says, nose wrinkled.

“It smells like the toilet,” the redhead girl sitting across from me pipes up.

Their eyes seem to simultaneously land on me, and I feel the heat and embarrassment of being different creep up my neck. Suddenly, a soggy old sandwich doesn’t seem so bad.

“What’s that green stuff?” the boy asks, blunt and direct, as kids tend to be, “I’ve never seen it before, but it looks and smells kinda yucky.” The huge lump in my throat prevents me from talking, but even if I wanted to, I don’t have the vocabulary yet to explain to him that it’s actually one of the best foods in the entire world.

The girl to my left answers for me. “It’s probably normal food for an Asian. Look, she has rice too, Asians always eat that.” To this day, it’s still beyond me how a five year old can recognize a different ethnicity, much less associate a food with it.

I go home that day and tell Mama I never want chives for lunch again. When she asks why, I tell her it’s because it smells like the toilet.

For years, I only bring store bought American food.

After that, I learn to hide behind a westernized mask by pretending my quickly unaccented English is my first and only language. Pretending I prefer the frozen prepackaged Costco burgers and Lunchables that everyone ate to my mother’s ethnic, seasoned dishes.

Pretending I had only ever known the American way of life when I missed the frequent sparkling fireworks, the feeling of my grandparents’ arms around me, the sense of belonging, more than words can describe.

__

I’m in sixth grade when my little brother comes home from kindergarten grade upset, near tears.

It takes much coaxing, but, eventually, in bits and pieces, the story comes out.

During their international unit in social studies, his teacher had asked which kids were bilingual, and my brother, along with a few other children in his class, had eagerly raised his hand, proud of being fluent in multiple languages. His teacher, who was monolingual, went down the line, having each child tell her their second or even third language.

“French.”

“Korean.”

“German.”

She had smiled at each, nodded perfunctorily.

When she reached my brother, he had proudly chirped, “Chinese. It’s one of the hardest languages in the world!” His teacher stopped then. Looked at him. Tilted her head and smiled like he was being naive.

“Honey,” she said gently, according to my brother, as if breaking bad news, “it’s not hard for a lot of people…” It wasn’t said, but I knew it was there: It’s not hard for an Asian.

My baby brother hadn’t caught on to the insinuation, he had simply been offended for having, what he considered, a great achievement of his be carelessly dismissed by someone whose approval he craved.

My brother was born and raised here. He has never lived in China, nor will he ever, but our father doesn’t allow us to speak English to him or my mother at home, so we can preserve our native tongue.

Surrounded constantly by English speakers at school, however, my brother and I typically converse in English, and he, having much less awareness, often turns to my parents as well and goes off on a rant in English.

My father usually calmly lets him finish before saying, mandarin syllables tumbling smoothly off his tongue, in a way my brother’s, and even mine, rarely did, “Say it in Chinese. We’re all Chinese here, why would you use a foreign language?”

I remember hearing his typical spiel about the importance of speaking Chinese once, just months after the chives incident, and feeling so frustrated I had screamed at him, “No one cares except for you! We live in America, Chinese is stupid, everyone thinks so, and I don’t need it!”

I genuinely hated it then.

English, to me, felt trendy, international, slipped out of my mouth as smooth as caramel. Chinese was awkward, bulky, mundane. It felt far more like chewing coffee beans.

The words must have stung, but he didn’t say anything back, he just remained silent until I grudgingly repeated myself in Chinese.

“Trust me,” he said quietly afterwards, the hurt clear in his tone, “Chinese or not, the gift of language is one of the greatest in the world. Being fluent is something you should be proud of. Your culture is something you should be proud of.”

And he was right, my brother’s pride in knowing the language of our ancestors shouldn’t have been dismissed. I don’t want him to learn to cope with the judgement the way I did at his age and often still do now.

___

It’s the end of seventh grade when one of my friends, while we are fixing ourselves up in the locker room after PE, looks in the mirror at me, studying, analyzing, before saying, “You know, you’re actually super pretty, especially for an Asian.” It’s not meant to be an insult in any way, simply an endearing observation. I force a smile and mutter “thank you,” unable to respond in any other way to the blatantly racist comment disguised by a compliment.

The bar used to judge beauty had been automatically lowered because I’m Asian.

She proceeds to list all the qualities of my face she liked, briefly and superficially repairing the damage she had done to my ego. She concludes her analysis of my face with, “If you got double eyelid surgery though, you would basically be perfect.”

She smiles kindly at me then, as if she had given me some sort of validation. As if saying, if not for the one shortcoming I had, the one belonging exclusively to my ethnicity, I would be beautiful.

What is the worst part, what hurts the most, as I think back years later, is how I distinctly remember nodding in agreement. I would be much prettier with double eyelids, like typical American girls, whose faces are composed of lines that connect in ways that seem fluid but defined, soft but bold, all at once.

Weeks later, I claim a sick day. Stay home from school spending hours perusing YouTube tutorials, trying to figure out a way to artificially induce double eyelids without surgery.

—

The summer before high school rushes by way too quickly in a flurry of freshly squeezed lemonade and painful sunburns, and the first day of school ambushes me before I can mentally prepare for it.

In my first class, I am approached by a cute guy, dirty blonde hair looking effortlessly windswept. He’s tall, sinewy. He introduces himself, then asks, hazel eyes twinkling, “Can I see your schedule? I want to see if we share any other classes.” I hand over my schedule and pick at my fingernails, freshly painted just for school, already bracing myself.

Exactly as I expect, he looks up half a minute later, previously flirtatious look replaced by a mixture of judgement and awe, “Damn, you’re taking all the highest-level courses? Do you not have any spare time for fun? Are you like, really smart, even for an Asian?”

I don’t even bother to defend myself at that point, simply suppress the urge to scream, chuckle and shrug modestly instead. Finding no other common classes, he quickly finds an excuse to leave, and, for the rest of the year, we only make awkward small talk when we have to.

—

For an Asian. Those, collectively, are my least favorite three words in the English language.

In my mind, those words bring with them the connotation of being a prude, being ugly, being insufficient. They imply that I’m not good enough, that any accomplishments that I do achieve can be easily dismissed.

They are the reason that, for years, I work hard at changing myself, changing my exterior to fit the status quo, to look and act more “normal.”

They are the reason that I westernized myself to the point where, years after my meltdown at the airport, when we finally return to China to visit, my beloved relatives can hardly recognize me with my strappy tank top, hoop earrings, lululemon leggings — hardly speaking, in shame of my now accented, long abandoned Chinese. I had only preserved the most basic of words to heedlessly satisfy my father.

When I am finally wrapped in my Po po’s arms once more, but with me, this time, towering over her small, shriveled body, the same warm florally scent she’d always worn encloses me. She says something then, and the Chinese words, like coffee beans once seeming so bulky and bitter, are now rich and warm again.

I have to ask her to repeat herself, however, more than once, as my rusted understanding of the language can no longer keep up with her emotional, accented dialect. And then, then is when I realize the extent of the damage I have done to the foundation of what makes me who I am.

We step into my childhood home, where my grandparents continue to live the last ten years that I have been gone, unwilling to leave the memories and emotions, even though they could have easily moved into a smaller, much nicer place with just the two of them.

The smell of chives rushes up, embracing me, welcoming me home. I glance at the table, where, just like all those years ago, fresh made chive dumplings await. Gong gong, back now bent with age, stands stooped over the kitchen counter rolling perfectly round wrapper after wrapper out of fresh dough, his hands still keen as ever.

He sees me, wraps me in a hug, and pushes me toward the table, “Go, go eat, I made your favorite.” He’s always been this way, communicating his love not through words, but through delicious concoctions. I don’t have the heart to tell him I have barely touched chives in the last ten years, unable to shake the memory of being called out for their putrid smell.

I tell myself to eat some just for his sake, and as I bite into one, and the memories burst through. Unfortunately, being chronically tainted with the bitterness of humiliation, it’s not as good as I remember it being, but the memories that come with it are. Exploding fireworks, bustling farmer’s markets, harassing the neighbors’ dogs. The nostalgia is overwhelming.

Before I know it, we’re all standing around the counter reminiscing, laughing, talking, eating, rolling out wrappers — my grandparents’ round, mine looking more like paint splatters.

But I am no longer punishing myself, no longer distancing myself from the culture of my ancestors for the sake of avoiding the ignorance and prejudice of others. Those three words: for an Asian, they still bother me, and I imagine they always will, but they no longer will me to change parts of myself. The American culture, it remains an integral part of me, but now the Chinese counterpart has become indispensable as well.

And the words that had become foreign, that felt like coffee beans in my mouth, they’ve started flowing more smoothly too. It’s not quite the consistency caramel yet, but it’s getting there.