My passion is painting, I have been painting since I was five years old (I’m now 20). I’ve recently found out my love for painting landscapes, the peacefulness it resonates in me is addictive! But I also love illustrating, I would always create fantasy characters before I learnt how to draw properly. I think what helps me in my journey and process of art is nature. Nature for me is art and art to me is spirit and exposure of the soul.

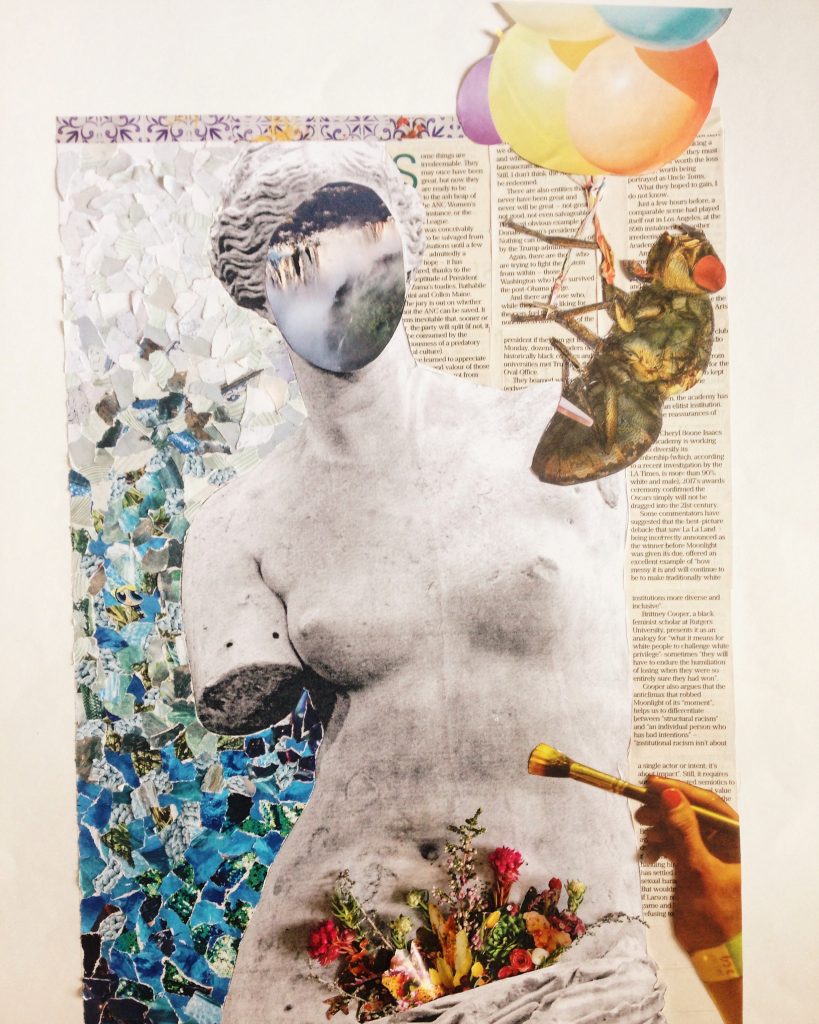

The acrylic mountains is a piece I did of a Drakensberg scenery, simply titled “Drakensberg” and the collage one is a recent piece I did titled “Media made”, focusing on the style surrealism with the theme of stereotypes and social media. Women are constantly being brushed to conform to societies appeal for “perfection” and roles a women should be actively participating in. In means of bodily perfection. I used magazine bits and the newspaper to identify the media, they have a role in how people act. Her face is unidentifiable since it’s not speaking to one person but rather a community of women being suppressed and undermined of our abilities. The flowers in her clothes are real dried flowers and represent our femininity.

Shannon Muller is from Durban South Africa, currently studying a bachelor of Fine Art and taking psychology as a subject at Rhodes University in Grahamstown Eastern Cape. She loves to read, paint landscapes in her free time and sit in coffee shops. She aspires to be an illustrator and is currently working on selling hand painted cards in local coffee shops. In the time she’s not studying she enjoys spending quality time with her family and her fiancé, this includes running and exploring her beautiful country.